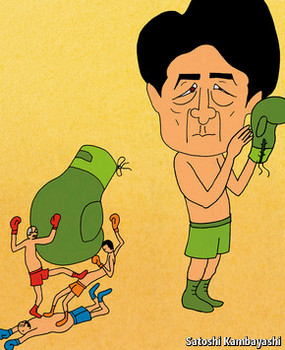

ひ弱な日本の野党 [政治]

★野党の足並みの乱れで余裕の表情の安倍首相

アベノミクスにも陰りが見えだした

イギリスの経済誌エコノミスト10月11日号はJapan’s feeble opposition(ひ弱な日本の野党)と題した記事を掲載、今の日本の政界、特に安倍政権の独走を許している野党の問題点など指摘しています。

英文記事を以下にまとめてみました。

「記事の内容」

東京、大阪、福岡などの大都会では安倍首相が掲げるアベノミクスという経済政策の恩恵を被っているようだが、それ以外の地方ではその恩恵にあずかれず安倍政権の経済政策に異を唱える人が次第に多くなってきている。

4月に導入した消費税8%アップによりGDPが第2四半期で7.1%も落ち込んでしまった。

そして安倍首相の人気にも次第に陰りが見えてきた。

有権者は野党に失望

野党が政権を狙う絶好の機会が到来?かと思いきや、有権者にとっては日本の野党は全くの期待外れとなっていて、有権者に大きな失望感を与えている。

それはどうしてなのか。

日本の野党はこれまで分裂と仲間割れを繰り返してきていている。

自民党が圧勝した2年前の選挙で政権の座から追い出されてしまった民主党やその他のミニ政党でも同じことが繰り替えされているのである。

そうした中で、2009年に自民党を抜け出した渡辺良美が設立したみんなの党に有権者の注目が集まったが、この党もまた渡辺氏の不適切な会計処理問題で大きく揺れ動いていて、国民の支持が得られていないのが実情だ。

代表の座を降りた渡辺氏と新代表の浅尾氏との間で確執が続いているようだ。

もう一人の悩める野党党首―民主党の海江田万里

海江田万里は2年前の選挙で民主党が大敗した危機を深刻に受け止めていない。

先月には海江田万里は党の執行部の人事を一新して党の代表の座にまた収まっているが、新執行部にはフレッシュな顔触れが見られない、それどころか女性の活用が全く見られない。

最大野党の民主党はアベノミクスに対抗すべく新たな経済政策を打ち出すのに苦労している中で、集団的自衛権の行使の是非を巡って党内で意見が割れている。

民主党の議員には厳格な平和主義者を唱える者が多いが、政府の動きに同調する現実主義路線の議員たちもいる。

来年予定されている集団的自衛権の立法化に民主党が賛成するかどうかが民主党が今後進むべき命運を分けることになりそうだ。

政府自民党はこの集団的自衛権の問題で民主党に揺さぶりをかけて民主党の動きを封じる狙いがある。

日本の政党はこれまで分裂しては新たな党を立ち上げては増殖してきたのだが、たとえあとから飛び出した党に戻ってきても離党の責任はそれほど厳しくは問われない。

今回政党から分かれて作られた多くのミニ政党から第3極の勢力が生まれると見ている人もいる。

橋下徹大阪市長率いる日本維新の会は結いの党と合併を果たしたが、原発、税、集団的自衛権などの重要問題をめぐっては意見の食い違いがまだまだ見られる。

民主党では保守派(市場保護派)と急進派(市場開放派)とに大きく分かれているが、急進派はみんなの党などのミニ政党と手を結べば自民党にとっても無視できない勢力となると見ている。

民主党は安倍首相の人気が高かった去年はアベノミクスを攻撃することは控えていたが、今はアベノミクスの金融緩和政策では賃金の上昇にうまくつながってはいない。

枝野幸男は安倍首相自身が安倍政権の最大の弱点であると見ている。安倍首相の自信過剰とも思える政治姿勢が災いして政権の座からの転落を招くことになると彼は考えている。

数多くのミニ野党はお互いに足の引っ張り合いをしていて、一致団結して安倍政権に立ち向かうという姿勢が見られない。

ここにきて連立与党の公明党の動きが気になる

公明党執行部は政府が掲げる集団的自衛権の行使を容認したが、母体となる創価学会の平和主義者や福祉政策派を完全には無視することは出来ない。

自民党内の反安倍勢力を甘く見てはいけない。

自民党内には今だに派閥勢力が根強く残っているのだ。

ハト派の議員たちは昨年12月の安倍首相の靖国神社参拝を激しく非難。

靖国神社参拝で日中関係が悪化しているが、それを鎮めるためかどうか自民党は谷垣氏を幹事長に起用し、反対派の懸念材料を払しょくする構えだ。

★このまま安倍政権の独走を許すのか、それとも各野党が一致団結してそれを阻止するのか、日本の有権者は政治の動向を厳しく見ていく必要がありそうです。

※記事の詳しい内容については以下の英文記事をご覧ください。

Japan’s feeble opposition

Not ready for prime time

The opposition struggles to counter a dominant prime minister

A RUN of dismal economic news has lessened the air of invincibility surrounding the government of Shinzo Abe, Japan’s prime minister. Outside the bustling metropolises such as Tokyo, Osaka and Fukuoka, ordinary people are growing more vocal in their complaints that Mr Abe’s schemes are doing little for them. A rise in the consumption (value-added) tax in April, meanwhile, seems to have knocked growth badly—GDP in the second quarter fell by an annualised 7.1%, for instance. All fertile ground, you would have thought, for an effective opposition. Yet if the shine is starting to come off Mr Abe’s popularity, the opposition to his Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) continues to be a crushing disappointment to voters.

Japan’s opposition parties have long been disunited and ill-disciplined. These flaws seem if anything to be deepening, whether inside the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), the biggest party, turfed out of government in an LDP landslide two years ago, or among a ragbag of smaller parties that surround the main two.

One outfit with early promise as a modernising force was Your Party, founded in 2009 by a defector from the LDP, Yoshimi Watanabe, son of a late LDP political heavyweight, and a rising star in the DPJ, Keiichiro Asao. Both chafed at the power of the bureaucracy and at the lack of market-minded attitudes in their respective parties; their new party appealed to younger professionals. Yet, in April, Mr Watanabe was forced to step down as party leader after he failed to account for how he spent a loan of ¥800m ($7.4m) from a friendly businessman. He is now calling for the resignation of Mr Asao, his successor as leader, for refusing to bring Your Party into alliance with Mr Abe, whose return to office in December 2012 Mr Watanabe supported. Weirdly, Mr Asao is putting up with the sniping.

Another troubled party boss is Banri Kaieda, head of the DPJ. For months, the party’s senior figures have been in open revolt. Mr Kaieda appears not to appreciate the depth of the crisis in which the party has found itself since its election defeat. Last month he managed to hang on to his position by reshuffling the party’s leadership to include some critics. But what many Japanese noticed in the new line-up of supposedly the most progressive mainstream party was a shortage of fresh talent and a complete absence of women. At least Mr Abe has five women in his cabinet, even if they are far from the most impressive women in politics.

While the DPJ struggles to propose alternative economic policies to Mr Abe’s, its leadership is split over his decision to reinterpret the constitution in order to give Japan the right to collective self-defence—coming to the aid of allies if attacked. The party has always had a large share of strict pacifists, but it also contains strategic realists who are strong supporters of the government’s move. Whether they will vote with the government when it tries to pass legislation on collective self-defence next year will be a stern test of party discipline, says Koichi Nakano of Sophia University in Tokyo. The LDP, for its part, aims to divide and permanently hobble the DPJ over the issue.

Japan’s political parties have long been fissiparous; politicians swerve off to found their own parties, as often as not coming back into the mainstream fold with little penalty. This time, some divine a potential “third force” in a slew of splits and envisioned alliances among the smaller parties. Yet nothing can conceal the policy chasms among these groupings. The Japan Restoration Party, headed by a self-regarding mayor of Osaka, Toru Hashimoto, last month merged with the far smaller Unity Party, a group of economic reformers. Yet the two sides continue to disagree over the big themes, including nuclear power, taxation and collective self-defence.

As for the DPJ, it seems torn between the market-illiberal, pro-union camp and market-minded reformists. Its modernisers hope that in alliance with a few smaller parties, such as Your Party, it might eventually become a force to be reckoned with again. It has plenty of cash to launch a comeback (the next general election is due by the end of 2016). There are signs that the party may go on the offensive at last. It held back from attacking Mr Abe’s economic programme during the height of its popularity last year, but now it is clear that the programme’s easy money has not succeeded in raising wages. The DPJ’s electoral strategist, Yukio Edano, reckons Mr Abe himself is the government’s chief weakness. The prime minister’s over-confidence, he claims, could set him up for a fall.

Just now, it is hard to think of a time when Japan’s formal opposition was less potent against the LDP. In fact, stronger restraints on Mr Abe probably come from the junior party in the ruling coalition, Komeito. Indeed, as a party founded on pacifism, it likes to describe itself as the LDP’s opposition. Though Komeito’s leadership eventually backed Mr Abe’s reform to allow collective self-defence, it cannot entirely ignore its pacifist and welfare-loving supporters in Soka Gakkai, a millions-strong lay Buddhist group.

And do not discount Mr Abe’s opposition within his own LDP. The party is still notable for the presence of powerful factions (though these are rarely formed along ideological lines). Moreover, many LDP members on its dovish wing expressed fury at Mr Abe’s visit last December to Tokyo’s Yasukuni shrine, which honours convicted war criminals alongside ordinary war dead. Relations with China, in particular, were damaged. In appointing Sadakazu Tanigaki, a pro-China liberal, as the LDP’s secretary-general, Mr Abe perhaps sought to head off his most threatening source of opposition.

コメント 0