脱原発は絵に描いた餅 [原発・原発事故]

福島第1原発が起きてから、3か月以上も経つというのに未だ収束の糸口が見えてこない。チェルノブイリ原発事故と深刻度が同じレベルになっているにもかかわらす゛、相変わらず原発推進を画策する政府と電力会社。原発を受けて入れている地域の住民からは表立った反対の声が上がってこないのはどうしてなのか。

外国では大規模な原発反対運動が起こっても不思議ではない。

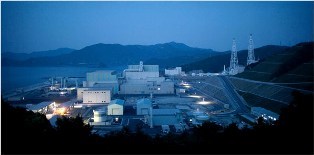

中国電力鹿島原発ー

現在、3号機が建設中

この問題をニューヨーク・タイムズの東京支局長であるマーチン・ファックラー氏がかなり詳しく記事にしています。日本のマスコミは政府や電力会社に遠慮しているのか、あまりここまで掘り下げて報道しないようです。

In Japan, a Culture That Promotes Nuclear Dependency

内容を簡単にまとめると次のようになると思います。

「政府からの手厚い交付金、保証金、そして仕事を与えることによって、電力会社は原発建設の賛同を地域住民から得ることが出来た。

こうした政府交付金は、地方の町や村の生活を豊かにしてきた。ところがいったん原発を受け入れてその交付金での豊かな生活に慣れてくると、その原発経済依存の体制から抜け出すことが難しくなり、ますます原発に頼るようになっていくのである。こうして原発経済依存の構造が出来上がり、原発に反対する声は隅の方に追いやられてしまうのである。

「原発は麻薬のようなもので、いったんそれを手に入れると必ずまた欲しくなるものだ」と言う人もいる。

地元が原発を受け入れるように促進するために出される政府交付金、そしてそれに頼る地方自治体。

この2つの歯車がかみ合って動いている日本経済、海外からはかなり批判の目で見られているようです。」

◆この記事を書いたマーチン・ファックラー氏は、週刊現代(7月9日号)で次のようなコメントを書いていますのでここに紹介しておきます。かなり手厳しい指摘をしていますが、我々日本人には大いに参考になるのではないでしょうか。

世界が見たニッポン 「政治もメディアもイカれてます」 ほかの国ではありえない

「日本はいくつもの深刻な原発事故を体験してきているのに、大規模な反対運動は起こらず、常に原発推進国であり続けた。ほかの国なら大規模な反対起こっているはずなのに、なぜ日本はそうならなかったのか。それが海外から見ると、不思議で仕方がなかったのです。

ところが取材の過程で、補助金と雇用創出につられて、原発のある街全体がそれに依存している仕組みが分かってきました。まるでドラッグのように、一度原発経済に依存してしまうと、もう抜け出せないーこれは私たちから見ると驚くべきことでした。

日本でも原発が建設されるまでは反対運動が起こるのですが、他の国とはそこからが違います。東海村の原発を例にとれば、1960年代~1970年代にかけて原発建設が進められたとき、地元の漁師たちが建設に反対しました。ところが、一度補助金・保証金が町に下りた途端、彼らは賛成派になってしまうのです。この変貌には驚きを禁じえません。いま、これらの地域を取材すると、住民が「原発事故は怖い。しかし、原発を誘致したことは後悔していない」と言うのですから、脱原発と口では言っても、現実的には難しいのではないでしょうか。」

※ このほかに、「国民の側に立たないメディア」、「菅も反菅もクレージー」といった記事も載せています。

In Japan, a Culture That Promotes Nuclear Dependency

By MARTIN FACKLER and NORIMITSU ONISHI

KASHIMA, Japan — When the Shimane nuclear plant was first proposed here more than 40 years ago, this rural port town put up such fierce resistance that the plant’s would-be operator, Chugoku Electric, almost scrapped the project. Angry fishermen vowed to defend areas where they had fished and harvested seaweed for generations.

Two decades later, when Chugoku Electric was considering whether to expand the plant with a third reactor, Kashima once again swung into action: this time, to rally in favor. Prodded by the local fishing cooperative, the town assembly voted 15 to 2 to make a public appeal for construction of the $4 billion reactor.

Kashima’s reversal is a common story in Japan, and one that helps explain what is, so far, this nation’s unwavering pursuit of nuclear power: a lack of widespread grass-roots opposition in the communities around its 54 nuclear reactors. This has held true even after the March 11 earthquake and tsunami generated a nuclear crisis at the Fukushima Daiichi station that has raised serious questions about whether this quake-prone nation has adequately ensured the safety of its plants. So far, it has spurred only muted public questioning in towns like this.

Prime Minister Naoto Kan has, at least temporarily, shelved plans to expand Japan’s use of nuclear power — plans promoted by the country’s powerful nuclear establishment. Communities appear willing to fight fiercely for nuclear power, despite concerns about safety that many residents refrain from voicing publicly.

To understand Kashima’s about-face, one need look no further than the Fukada Sports Park, which serves the 7,500 mostly older residents here with a baseball diamond, lighted tennis courts, a soccer field and a $35 million gymnasium with indoor pool and Olympic-size volleyball arena. The gym is just one of several big public works projects paid for with the hundreds of millions of dollars this community is receiving for accepting the No. 3 reactor, which is still under construction.

As Kashima’s story suggests, Tokyo has been able to essentially buy the support, or at least the silent acquiescence, of communities by showering them with generous subsidies, payouts and jobs. In 2009 alone, Tokyo gave $1.15 billion for public works projects to communities that have electric plants, according to the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. Experts say the majority of that money goes to communities near nuclear plants.

And that is just the tip of the iceberg, experts say, as the communities also receive a host of subsidies, property and income tax revenues, compensation to individuals and even “anonymous” donations to local treasuries that are widely believed to come from plant operators.

Unquestionably, the aid has enriched rural communities that were rapidly losing jobs and people to the cities. With no substantial reserves of oil or coal, Japan relies on nuclear power for the energy needed to drive its economic machine. But critics contend that the largess has also made communities dependent on central government spending — and thus unwilling to rock the boat by pushing for robust safety measures.

In a process that critics have likened to drug addiction, the flow of easy money and higher-paying jobs quickly replaces the communities’ original economic basis, usually farming or fishing.

Nor did planners offer alternatives to public works projects like nuclear plants. Keeping the spending spigots open became the only way to maintain newly elevated living standards.

Experts and some residents say this dependency helps explain why, despite the legacy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the accidents at the Three Mile Island and Chernobyl nuclear plants, Japan never faced the levels of popular opposition to nuclear power seen in the United States and Europe — and is less likely than the United States to stop building new plants. Towns become enmeshed in the same circle — which includes politicians, bureaucrats, judges and nuclear industry executives — that has relentlessly promoted the expansion of nuclear power over safety concerns.

“This structure of dependency makes it impossible for communities to speak out against the plants or nuclear power,” said Shuji Shimizu, a professor of public finance at Fukushima University.

Code of Silence

Indeed, a code of silence seems to prevail even now in towns like Kashima, which merged with the neighboring city of Matsue a half decade ago.

Tsuneyoshi Adachi, a 63-year-old fisherman, joined the huge protests in the 1970s and 1980s against the plant’s No. 2 reactor. He said many fishermen were angry then because chlorine from the pumps of the plant’s No. 1 reactor, which began operating in 1974, was killing seaweed and fish in local fishing grounds.

However, Mr. Adachi said, once compensation payments from the No. 2 reactor began to flow in, neighbors began to give him cold looks and then ignore him. By the time the No. 3 reactor was proposed in the early 1990s, no one, including Mr. Adachi, was willing to speak out against the plant. He said that there was the same peer pressure even after the accident at Fukushima, which scared many here because they live within a few miles of the Shimane plant.

“Sure, we are all worried in our hearts about whether the same disaster could happen at the Shimane nuclear plant,” Mr. Adachi said. However, “the town knows it can no longer survive economically without the nuclear plant.”

While few will say so in public, many residents also quietly express concern about how their town gave up its once-busy fishing industry. They also say that flashy projects like the sports park have brought little lasting economic benefit. The No. 3 reactor alone brought the town some $90 million in public works money, and the promise of another $690 million in property tax revenues spread over more than 15 years once the reactor becomes operational next year.

In the 1990s, property taxes from the No. 2 reactor supplied as much as three-quarters of town tax revenues. The fact that the revenues were going to decline eventually was one factor that drove the town to seek the No. 3 reactor, said the mayor at the time, Zentaro Aoyama.

Mr. Aoyama admitted that the Fukushima accident had frightened many people here. Even so, he said, the community had no regrets about accepting the Shimane plant, which he said had raised living standards and prevented the depopulation that has hollowed out much of rural Japan.

“What would have happened here without the plant?” said Mr. Aoyama, 73, who said the town used its very first compensation payment from the No. 1 reactor back in the late 1960s to install indoor plumbing.

While the plants provide power mostly to distant urban areas, they were built in isolated, impoverished rural areas.

Kazuyoshi Nakamura, 84, recalls how difficult life was as a child in Kataku, a tiny fishing hamlet within Kashima that faces the rough Sea of Japan. His father used a tiny wooden skiff to catch squid and bream, which his mother carried on her back to market, walking narrow mountain paths in straw sandals.

Still, at first local fishermen adamantly refused to give up rights to the seaweed and fishing grounds near the plant, said Mr. Nakamura, who was a leader of Kataku’s fishing cooperative at the time. They eventually accepted compensation payments that have totaled up to $600,000 for each fisherman.

“In the end, we gave in for money,” Mr. Nakamura said.

Today, the dirt-floor huts of Mr. Nakamura’s childhood have been replaced by oversize homes with driveways, and a tunnel has made central Kashima a five-minute drive away. But the new wealth has changed this hamlet of almost 300 in unforeseen ways. Only about 30 aging residents still make a living from fishing. Many of the rest now commute to the plant, where they work as security guards or cleaners.

“There was no need to work anymore because the money just flowed so easily,” said a former town assemblyman who twice ran unsuccessfully for mayor on an antinuclear platform.

A Flow of Cash

Much of this flow of cash was the product of the Three Power Source Development Laws, a sophisticated system of government subsidies created in 1974 by Kakuei Tanaka, the powerful prime minister who shaped Japan’s nuclear power landscape and used big public works projects to build postwar Japan’s most formidable political machine.

The law required all Japanese power consumers to pay, as part of their utility bills, a tax that was funneled to communities with nuclear plants. Officials at the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, which regulates the nuclear industry, and oversees the subsidies, refused to specify how much communities have come to rely on those subsidies.

“This is money to promote the locality’s acceptance of a nuclear plant,” said Tatsumi Nakano of the ministry’s Agency for Natural Resources and Energy. A spokesman for Tohoku Electric Power Company, which operates a plant in Higashidori, said that the company is not involved in the subsidies, and that since Fukushima, it has focused on reassuring the public of the safety of nuclear plants.

Political experts say the subsidies encourage not only acceptance of a plant but also, over time, its expansion. That is because subsidies are designed to peak soon after a plant or reactor becomes operational, and then decline.

“In many cases, what you’ll see is that a town that was depopulating and had very little tax base gets a tremendous insurge of money,” said Daniel P. Aldrich, a political scientist at Purdue University who has studied the laws.

As the subsidies continue to decline over the lifetime of a reactor, communities come under pressure to accept the construction of new ones, Mr. Aldrich said. “The local community gets used to the spending they got for the first reactor — and the second, third, fourth, and fifth reactors help them keep up,” he added.

Critics point to the case of Futaba, the town that includes Fukushima Daiichi’s No. 5 and No. 6 reactors, which began operating in 1978 and 1979, respectively.

According to Professor Shimizu of Fukushima University, Fukushima Daiichi and the nearby Fukushima Daini plants directly or indirectly employed some 11,000 people in communities that include Futaba — or about one person in every two households. Since 1974, communities in Fukushima Prefecture have received about $3.3 billion in subsidies for its electrical plants, most of it for the two nuclear power facilities, Mr. Shimizu said.

Despite these huge subsidies, most given in the 1970s, Futaba recently began to experience budget problems. As they did in Kashima, the subsidies dwindled along with other revenues related to the nuclear plant, including property taxes. By 2007, Futaba was one of the most fiscally troubled towns in Japan and nearly went bankrupt. Town officials blamed the upkeep costs of the public facilities built in the early days of flush subsidies and poor management stemming from the belief that the subsidies would remain generous.

Eisaku Sato, who served as the governor of Fukushima Prefecture from 1988 to 2006 and became a critic of the nuclear industry, said that 30 years after its first reactor started operating, the town of Futaba could no longer pay its mayor’s salary.

“With a nuclear reactor, in one generation, or about 30 years, it’s possible that you’ll become a community that won’t be able to survive,” Mr. Sato said.

Futaba’s solution to its fiscal crisis was to ask the government and Tokyo Electric, Fukushima Daiichi’s operator, to build two new reactors, which would have eventually increased the number of reactors at Fukushima Daiichi to eight. The request immediately earned Futaba new subsidies.

“Putting aside whether ‘drugs’ is the right expression,” Mr. Sato said, “if you take them one time, you’ll definitely want to take them again.”

Eiji Nakamura, the failed candidate for mayor of Kashima, said the town came to rely on the constant flow of subsidies for political as well as economic reasons. He said the prefectural and town leaders used the jobs and money from public works to secure the support of key voting blocs like the construction industry and the fishing cooperative, to which about a third of the town’s working population belongs.

“They call it a nuclear power plant, but it should actually be called a political power plant,” Mr. Nakamura joked.

The Most to Lose

This dependence explains why Prime Minister Kan’s talk of slowing Japan’s push for nuclear power worries few places as much as the Shimokita Peninsula, an isolated region in northern Honshu.

The peninsula’s first reactor went online in 2005, two are under construction, and two more are still being planned. Japan is also building massive nuclear waste disposal and reprocessing facilities there. As newcomers to nuclear power, Shimokita’s host communities now have the most to lose.

Consider Higashidori, a town with one working reactor and three more scheduled to start operating over the next decade. With the subsidies and other revenues from four planned reactors, town officials began building an entirely new town center two decades ago.

Serving a rapidly declining population of 7,300, the town center is now dominated by three gigantic, and barely used, buildings in the shape of a triangle, a circle and a square, which, according to the Tokyo-based designer, symbolize man, woman and child. Nearby, a sprawling campus with two running tracks, two large gymnasiums, eight tennis courts and an indoor baseball field serves fewer than 600 elementary and junior high school children. In 2010, nearly 46 percent of the town’s $94 million budget came from nuclear-related subsidies and property taxes.

Shigenori Sasatake, a town official overseeing nuclear power, said Higashidori hoped that the Japanese government and plant operators would not waver from their commitment to build three more reactors there, despite the risks exposed at Fukushima.

“Because there are risks, there is no way reactors would be built in Tokyo, but only here in this kind of rural area,” Mr. Sasatake said, adding that town officials harbored no regrets about having undertaken such grandiose building projects.

But Higashidori’s building spree raised eyebrows in Oma, another peninsula town, with 6,300 residents, where construction on its first reactor, scheduled to start operating in 2014, was halted after the Fukushima disaster.

Tsuneyoshi Asami, a former mayor who played a critical role in bringing the plant to Oma, said that the town did not want to be stuck with fancy but useless buildings that would create fiscal problems in the future. So far, Oma has resisted building a new town hall, using nuclear subsidies instead to construct educational and fisheries facilities, as well as a home for the elderly.

“Regular people and town council members kept saying that no other community where a plant was located has stopped at only one reactor — that there was always a second or third one — so we should be spending more,” Mr. Asami said. “But I said no.”

Still, even in Oma, there were worries that the Fukushima disaster would indefinitely delay the construction of its plant. It is just the latest example of how the system of subsidies and dependency Japan created to expand nuclear power makes it difficult for the country to reverse course.

“We absolutely need it,” Yoshifumi Matsuyama, the chairman of Oma’s Chamber of Commerce, said of the plant. “Nothing other than a nuclear plant will bring money here. That’s for sure. What else can an isolated town like this do except host a nuclear plant?”

外国では大規模な原発反対運動が起こっても不思議ではない。

中国電力鹿島原発ー

現在、3号機が建設中

この問題をニューヨーク・タイムズの東京支局長であるマーチン・ファックラー氏がかなり詳しく記事にしています。日本のマスコミは政府や電力会社に遠慮しているのか、あまりここまで掘り下げて報道しないようです。

In Japan, a Culture That Promotes Nuclear Dependency

内容を簡単にまとめると次のようになると思います。

「政府からの手厚い交付金、保証金、そして仕事を与えることによって、電力会社は原発建設の賛同を地域住民から得ることが出来た。

こうした政府交付金は、地方の町や村の生活を豊かにしてきた。ところがいったん原発を受け入れてその交付金での豊かな生活に慣れてくると、その原発経済依存の体制から抜け出すことが難しくなり、ますます原発に頼るようになっていくのである。こうして原発経済依存の構造が出来上がり、原発に反対する声は隅の方に追いやられてしまうのである。

「原発は麻薬のようなもので、いったんそれを手に入れると必ずまた欲しくなるものだ」と言う人もいる。

地元が原発を受け入れるように促進するために出される政府交付金、そしてそれに頼る地方自治体。

この2つの歯車がかみ合って動いている日本経済、海外からはかなり批判の目で見られているようです。」

◆この記事を書いたマーチン・ファックラー氏は、週刊現代(7月9日号)で次のようなコメントを書いていますのでここに紹介しておきます。かなり手厳しい指摘をしていますが、我々日本人には大いに参考になるのではないでしょうか。

世界が見たニッポン 「政治もメディアもイカれてます」 ほかの国ではありえない

「日本はいくつもの深刻な原発事故を体験してきているのに、大規模な反対運動は起こらず、常に原発推進国であり続けた。ほかの国なら大規模な反対起こっているはずなのに、なぜ日本はそうならなかったのか。それが海外から見ると、不思議で仕方がなかったのです。

ところが取材の過程で、補助金と雇用創出につられて、原発のある街全体がそれに依存している仕組みが分かってきました。まるでドラッグのように、一度原発経済に依存してしまうと、もう抜け出せないーこれは私たちから見ると驚くべきことでした。

日本でも原発が建設されるまでは反対運動が起こるのですが、他の国とはそこからが違います。東海村の原発を例にとれば、1960年代~1970年代にかけて原発建設が進められたとき、地元の漁師たちが建設に反対しました。ところが、一度補助金・保証金が町に下りた途端、彼らは賛成派になってしまうのです。この変貌には驚きを禁じえません。いま、これらの地域を取材すると、住民が「原発事故は怖い。しかし、原発を誘致したことは後悔していない」と言うのですから、脱原発と口では言っても、現実的には難しいのではないでしょうか。」

※ このほかに、「国民の側に立たないメディア」、「菅も反菅もクレージー」といった記事も載せています。

In Japan, a Culture That Promotes Nuclear Dependency

By MARTIN FACKLER and NORIMITSU ONISHI

KASHIMA, Japan — When the Shimane nuclear plant was first proposed here more than 40 years ago, this rural port town put up such fierce resistance that the plant’s would-be operator, Chugoku Electric, almost scrapped the project. Angry fishermen vowed to defend areas where they had fished and harvested seaweed for generations.

Two decades later, when Chugoku Electric was considering whether to expand the plant with a third reactor, Kashima once again swung into action: this time, to rally in favor. Prodded by the local fishing cooperative, the town assembly voted 15 to 2 to make a public appeal for construction of the $4 billion reactor.

Kashima’s reversal is a common story in Japan, and one that helps explain what is, so far, this nation’s unwavering pursuit of nuclear power: a lack of widespread grass-roots opposition in the communities around its 54 nuclear reactors. This has held true even after the March 11 earthquake and tsunami generated a nuclear crisis at the Fukushima Daiichi station that has raised serious questions about whether this quake-prone nation has adequately ensured the safety of its plants. So far, it has spurred only muted public questioning in towns like this.

Prime Minister Naoto Kan has, at least temporarily, shelved plans to expand Japan’s use of nuclear power — plans promoted by the country’s powerful nuclear establishment. Communities appear willing to fight fiercely for nuclear power, despite concerns about safety that many residents refrain from voicing publicly.

To understand Kashima’s about-face, one need look no further than the Fukada Sports Park, which serves the 7,500 mostly older residents here with a baseball diamond, lighted tennis courts, a soccer field and a $35 million gymnasium with indoor pool and Olympic-size volleyball arena. The gym is just one of several big public works projects paid for with the hundreds of millions of dollars this community is receiving for accepting the No. 3 reactor, which is still under construction.

As Kashima’s story suggests, Tokyo has been able to essentially buy the support, or at least the silent acquiescence, of communities by showering them with generous subsidies, payouts and jobs. In 2009 alone, Tokyo gave $1.15 billion for public works projects to communities that have electric plants, according to the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. Experts say the majority of that money goes to communities near nuclear plants.

And that is just the tip of the iceberg, experts say, as the communities also receive a host of subsidies, property and income tax revenues, compensation to individuals and even “anonymous” donations to local treasuries that are widely believed to come from plant operators.

Unquestionably, the aid has enriched rural communities that were rapidly losing jobs and people to the cities. With no substantial reserves of oil or coal, Japan relies on nuclear power for the energy needed to drive its economic machine. But critics contend that the largess has also made communities dependent on central government spending — and thus unwilling to rock the boat by pushing for robust safety measures.

In a process that critics have likened to drug addiction, the flow of easy money and higher-paying jobs quickly replaces the communities’ original economic basis, usually farming or fishing.

Nor did planners offer alternatives to public works projects like nuclear plants. Keeping the spending spigots open became the only way to maintain newly elevated living standards.

Experts and some residents say this dependency helps explain why, despite the legacy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the accidents at the Three Mile Island and Chernobyl nuclear plants, Japan never faced the levels of popular opposition to nuclear power seen in the United States and Europe — and is less likely than the United States to stop building new plants. Towns become enmeshed in the same circle — which includes politicians, bureaucrats, judges and nuclear industry executives — that has relentlessly promoted the expansion of nuclear power over safety concerns.

“This structure of dependency makes it impossible for communities to speak out against the plants or nuclear power,” said Shuji Shimizu, a professor of public finance at Fukushima University.

Code of Silence

Indeed, a code of silence seems to prevail even now in towns like Kashima, which merged with the neighboring city of Matsue a half decade ago.

Tsuneyoshi Adachi, a 63-year-old fisherman, joined the huge protests in the 1970s and 1980s against the plant’s No. 2 reactor. He said many fishermen were angry then because chlorine from the pumps of the plant’s No. 1 reactor, which began operating in 1974, was killing seaweed and fish in local fishing grounds.

However, Mr. Adachi said, once compensation payments from the No. 2 reactor began to flow in, neighbors began to give him cold looks and then ignore him. By the time the No. 3 reactor was proposed in the early 1990s, no one, including Mr. Adachi, was willing to speak out against the plant. He said that there was the same peer pressure even after the accident at Fukushima, which scared many here because they live within a few miles of the Shimane plant.

“Sure, we are all worried in our hearts about whether the same disaster could happen at the Shimane nuclear plant,” Mr. Adachi said. However, “the town knows it can no longer survive economically without the nuclear plant.”

While few will say so in public, many residents also quietly express concern about how their town gave up its once-busy fishing industry. They also say that flashy projects like the sports park have brought little lasting economic benefit. The No. 3 reactor alone brought the town some $90 million in public works money, and the promise of another $690 million in property tax revenues spread over more than 15 years once the reactor becomes operational next year.

In the 1990s, property taxes from the No. 2 reactor supplied as much as three-quarters of town tax revenues. The fact that the revenues were going to decline eventually was one factor that drove the town to seek the No. 3 reactor, said the mayor at the time, Zentaro Aoyama.

Mr. Aoyama admitted that the Fukushima accident had frightened many people here. Even so, he said, the community had no regrets about accepting the Shimane plant, which he said had raised living standards and prevented the depopulation that has hollowed out much of rural Japan.

“What would have happened here without the plant?” said Mr. Aoyama, 73, who said the town used its very first compensation payment from the No. 1 reactor back in the late 1960s to install indoor plumbing.

While the plants provide power mostly to distant urban areas, they were built in isolated, impoverished rural areas.

Kazuyoshi Nakamura, 84, recalls how difficult life was as a child in Kataku, a tiny fishing hamlet within Kashima that faces the rough Sea of Japan. His father used a tiny wooden skiff to catch squid and bream, which his mother carried on her back to market, walking narrow mountain paths in straw sandals.

Still, at first local fishermen adamantly refused to give up rights to the seaweed and fishing grounds near the plant, said Mr. Nakamura, who was a leader of Kataku’s fishing cooperative at the time. They eventually accepted compensation payments that have totaled up to $600,000 for each fisherman.

“In the end, we gave in for money,” Mr. Nakamura said.

Today, the dirt-floor huts of Mr. Nakamura’s childhood have been replaced by oversize homes with driveways, and a tunnel has made central Kashima a five-minute drive away. But the new wealth has changed this hamlet of almost 300 in unforeseen ways. Only about 30 aging residents still make a living from fishing. Many of the rest now commute to the plant, where they work as security guards or cleaners.

“There was no need to work anymore because the money just flowed so easily,” said a former town assemblyman who twice ran unsuccessfully for mayor on an antinuclear platform.

A Flow of Cash

Much of this flow of cash was the product of the Three Power Source Development Laws, a sophisticated system of government subsidies created in 1974 by Kakuei Tanaka, the powerful prime minister who shaped Japan’s nuclear power landscape and used big public works projects to build postwar Japan’s most formidable political machine.

The law required all Japanese power consumers to pay, as part of their utility bills, a tax that was funneled to communities with nuclear plants. Officials at the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, which regulates the nuclear industry, and oversees the subsidies, refused to specify how much communities have come to rely on those subsidies.

“This is money to promote the locality’s acceptance of a nuclear plant,” said Tatsumi Nakano of the ministry’s Agency for Natural Resources and Energy. A spokesman for Tohoku Electric Power Company, which operates a plant in Higashidori, said that the company is not involved in the subsidies, and that since Fukushima, it has focused on reassuring the public of the safety of nuclear plants.

Political experts say the subsidies encourage not only acceptance of a plant but also, over time, its expansion. That is because subsidies are designed to peak soon after a plant or reactor becomes operational, and then decline.

“In many cases, what you’ll see is that a town that was depopulating and had very little tax base gets a tremendous insurge of money,” said Daniel P. Aldrich, a political scientist at Purdue University who has studied the laws.

As the subsidies continue to decline over the lifetime of a reactor, communities come under pressure to accept the construction of new ones, Mr. Aldrich said. “The local community gets used to the spending they got for the first reactor — and the second, third, fourth, and fifth reactors help them keep up,” he added.

Critics point to the case of Futaba, the town that includes Fukushima Daiichi’s No. 5 and No. 6 reactors, which began operating in 1978 and 1979, respectively.

According to Professor Shimizu of Fukushima University, Fukushima Daiichi and the nearby Fukushima Daini plants directly or indirectly employed some 11,000 people in communities that include Futaba — or about one person in every two households. Since 1974, communities in Fukushima Prefecture have received about $3.3 billion in subsidies for its electrical plants, most of it for the two nuclear power facilities, Mr. Shimizu said.

Despite these huge subsidies, most given in the 1970s, Futaba recently began to experience budget problems. As they did in Kashima, the subsidies dwindled along with other revenues related to the nuclear plant, including property taxes. By 2007, Futaba was one of the most fiscally troubled towns in Japan and nearly went bankrupt. Town officials blamed the upkeep costs of the public facilities built in the early days of flush subsidies and poor management stemming from the belief that the subsidies would remain generous.

Eisaku Sato, who served as the governor of Fukushima Prefecture from 1988 to 2006 and became a critic of the nuclear industry, said that 30 years after its first reactor started operating, the town of Futaba could no longer pay its mayor’s salary.

“With a nuclear reactor, in one generation, or about 30 years, it’s possible that you’ll become a community that won’t be able to survive,” Mr. Sato said.

Futaba’s solution to its fiscal crisis was to ask the government and Tokyo Electric, Fukushima Daiichi’s operator, to build two new reactors, which would have eventually increased the number of reactors at Fukushima Daiichi to eight. The request immediately earned Futaba new subsidies.

“Putting aside whether ‘drugs’ is the right expression,” Mr. Sato said, “if you take them one time, you’ll definitely want to take them again.”

Eiji Nakamura, the failed candidate for mayor of Kashima, said the town came to rely on the constant flow of subsidies for political as well as economic reasons. He said the prefectural and town leaders used the jobs and money from public works to secure the support of key voting blocs like the construction industry and the fishing cooperative, to which about a third of the town’s working population belongs.

“They call it a nuclear power plant, but it should actually be called a political power plant,” Mr. Nakamura joked.

The Most to Lose

This dependence explains why Prime Minister Kan’s talk of slowing Japan’s push for nuclear power worries few places as much as the Shimokita Peninsula, an isolated region in northern Honshu.

The peninsula’s first reactor went online in 2005, two are under construction, and two more are still being planned. Japan is also building massive nuclear waste disposal and reprocessing facilities there. As newcomers to nuclear power, Shimokita’s host communities now have the most to lose.

Consider Higashidori, a town with one working reactor and three more scheduled to start operating over the next decade. With the subsidies and other revenues from four planned reactors, town officials began building an entirely new town center two decades ago.

Serving a rapidly declining population of 7,300, the town center is now dominated by three gigantic, and barely used, buildings in the shape of a triangle, a circle and a square, which, according to the Tokyo-based designer, symbolize man, woman and child. Nearby, a sprawling campus with two running tracks, two large gymnasiums, eight tennis courts and an indoor baseball field serves fewer than 600 elementary and junior high school children. In 2010, nearly 46 percent of the town’s $94 million budget came from nuclear-related subsidies and property taxes.

Shigenori Sasatake, a town official overseeing nuclear power, said Higashidori hoped that the Japanese government and plant operators would not waver from their commitment to build three more reactors there, despite the risks exposed at Fukushima.

“Because there are risks, there is no way reactors would be built in Tokyo, but only here in this kind of rural area,” Mr. Sasatake said, adding that town officials harbored no regrets about having undertaken such grandiose building projects.

But Higashidori’s building spree raised eyebrows in Oma, another peninsula town, with 6,300 residents, where construction on its first reactor, scheduled to start operating in 2014, was halted after the Fukushima disaster.

Tsuneyoshi Asami, a former mayor who played a critical role in bringing the plant to Oma, said that the town did not want to be stuck with fancy but useless buildings that would create fiscal problems in the future. So far, Oma has resisted building a new town hall, using nuclear subsidies instead to construct educational and fisheries facilities, as well as a home for the elderly.

“Regular people and town council members kept saying that no other community where a plant was located has stopped at only one reactor — that there was always a second or third one — so we should be spending more,” Mr. Asami said. “But I said no.”

Still, even in Oma, there were worries that the Fukushima disaster would indefinitely delay the construction of its plant. It is just the latest example of how the system of subsidies and dependency Japan created to expand nuclear power makes it difficult for the country to reverse course.

“We absolutely need it,” Yoshifumi Matsuyama, the chairman of Oma’s Chamber of Commerce, said of the plant. “Nothing other than a nuclear plant will bring money here. That’s for sure. What else can an isolated town like this do except host a nuclear plant?”

コメント 0